Ok, now it is time to take a deeper look at the military road located on the back side of Prospect Hill and how it was associated with Lieutenant Colonel Reuben L. Walker’s artillery battalion gun emplacements. Walker himself was considered a premier artillerist.

If you have ever visited Prospect Hill, you would assume that the park road, Lee Drive, is the original road dating from around the time of the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862. You could imagine the Confederate batteries moving along the road from Hamilton’s Crossing, guiding their horse teams that were pulling the limbers and guns, the gun crews running alongside unhitching their guns and rolling them into place. Each horse team with its limber would be neatly looped around facing the gun while the gun crew of five prepared to fire.

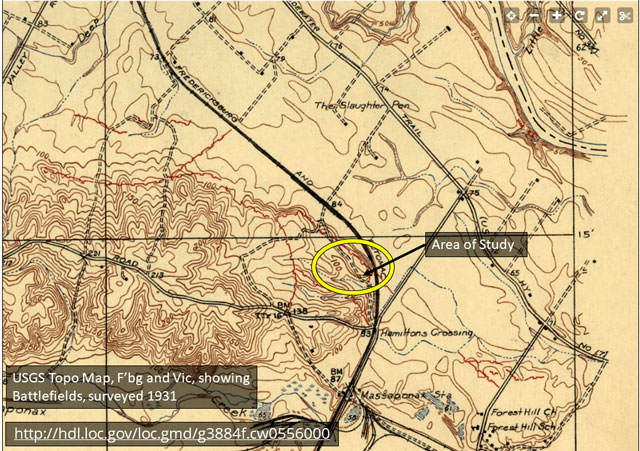

However, looking over the 1931 United States Geological Survey (USGS) map of the battlefield, I was quickly dissuaded of Lee Drive being the original road. In fact, I made four visits to look for the original road. At first, I believed that I was looking for a trail. I even found what I believed to be the overused trail that had become severely eroded. This trail would need to have been a minimum of seven feet (2.1 meters) wide to accommodate a six-foot wide (1.8 meters) gun carriage. It was not until I realized I was thinking too small and should instead be looking for a road!

This map shows the terrain and roads prior to the creation of the National Park. Within the yellow circle, you can see that the road sidestepped the hill to the west to cross the terrain, avoiding the steep slope found on the south and east sides of Prospect Hill. This road originated with local landowners of the late 1700’s and early 1800’s as they developed the region. It was coopted by the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia when they occupied the area during and after the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. This road led to Hamilton’s Crossing of Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad (FR&P) and to Mine Road and Captain Hamilton’s home.

When Congress established Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Park (FSNMP) in 1925, they placed it under the management of the War Department (click here). The park road they constructed, Lee Drive, followed the line of entrenchments and artillery gun positions. On the southern end of Prospect Hill, it was necessary to excavate a road cut to stay relatively close to the artillery gun emplacements and to gently slope the road downhill.

I can remember being able to drive on it all the way to Hamilton’s Crossing in the late 1970’s. The Park Service closed this off in the 1990’s causing motorists to turn around at NPS Stop #6.

Recently, the National Park Service (NPS) contracted a LiDAR (an acronym of “light detection and ranging”) image of Prospect Hill. This image is superimposed on the USGS topography on top of that image. I highlighted the original landowner created road in yellow. Notice how it skirts the hill to the west and joins the road to Hamilton’s Crossing on the right side of the image. When the new park road was constructed, they also obliterated the original road, possibly to keep visitors mistaking it for the new road, Lee Drive.

In the enlarged view, the road trace is aligned with this eroded ditch. You can make out another road ditch parallel and below it. The roadway is in between.

I was curious to see if any of that roadway still existed. The LiDAR image indicated that a portion might remain. Removing the topo overlay, on the now clear image (right side) you can see the Walker’s gun emplacements in red along the crest of the hill, the park boundary in green, with the RF&P railroad running in between, roads are in purple and trails in brown. Generally, LiDAR simply provides a trace of a road rather than its full width. In the upper left, you can see where Lee Drive pulls into the ‘Stop #6’ parking area and then loops back on itself. The park service blocked access to the road continuation in the 1990’s. Its continuation is in brown, indicating that one can hike here. Look closely on the shoulder of the trail in shadow, and you can make out the excavated cut.

Now look at the purple oval in the lower center, and then at the enlarged LiDAR image to the left. The road trace in purple runs right through a darker shadow area. This seemed to indicate where there was erosion. This is where I erroneously believed that I’d found a logging trail used to run the guns up on top of the hill.

I next went to Google Earth looking for the same region of Prospect Hill. I discovered precisely the same thing. On the right aerial photo, dated December 31, 2007, at almost the same scale as the LiDAR image, is a shadow of the eroded ditch (see the purple oval). Lee Drive and Stop #6 are on the upper left. A spot elevation of 132 feet (40 meters) is in yellow. In the enlarged view, you can make out the eroded ditch plus a tree that has fallen across the roadbed. You can also make out a faint second roadside ditch parallel with the first eroded ditch. The roadbed is in between the two.

I went to the field in January and February to check this out. Using the enlarged LiDAR image to note the photo locations, here are my results.

Approaching the area from the road leading to Hamilton’s Crossing, I found the log that had fallen across the roadbed, with the severely eroded drainage ditch beyond on the right. Just beyond the log, note the orange cones which I placed at 5-step intervals on the left side and the orange flags on the right of the roadbed to mark the road.

Crossing over the fallen log, I looked in the opposite direction. This time, the flags are on the right side. These mark a drainage ditch on the other side of the roadbed. The severely eroded drainage ditch marked by the orange cones is on the left side of this photo. The road is approximately 15 feet (4.5 meters) wide.

Turning 180 degrees around at this spot, you can make out the continuation of the roadbed. Cones are on the right and flags are on the left. I laid my yellow rake down in an area where I looked for the roadbed itself. All I found was evidence of years of fallen leaves that were turning into soil.

At the location of photo D, the roadbed pivots to the east about 30 degrees. When I walked beyond the last of the cones/flags going onto Park Stop #6, I found a slight ditch on the uphill side that indicated the continued alignment of the original road. This became indistinct as I reached that parking lot.

I’ve overlayed the road alignment on top of the Google Earth aerial photo. You can see the confirmed and probable alignment of the road.

So, how is this connected to the Walker’s Confederate gun emplacements one might ask? For that, I turn to some of the participants to paint a picture.

Captain William Thomas Poague gives us the following account of his action in the early afternoon of December 13, 1862. Colonel J. Thompson Brown’s reserve artillery were stationed along Mine Run near Hamilton’s house during the morning of the battle. Jackson’s artillery chief, Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield, ordered Brown to send relief to Walker on Prospect Hill.

“…Colonel Brown was ordered to relieve Lindsay Walker’s Battalion which had been badly smashed up on what was afterwards known as Dead Horse Hill. My guns (two 20-pound Parrot rifles) were at the head of the column and with me was riding Dr. Hayslett. As we began the ascent of the hill there came tearing down through the woods towards us a horseman bareheaded with handkerchief around his forehead, a short pipe in his mouth and suddenly reining up, called out ‘where are you all going?’ and as I told him ‘to take the place of Walker’s Battalion’ he fairly shouted, ‘good for you; we need you! We’re knocked all to pieces! Isn’t this fun!’ As he turned his horse and galloped back, Hayslett broke out with one of his noted big laughs, ‘Well, that fellow must be crazy, don’t you think?’ I replied: ‘He’s all right, that’s Ham Chamberlayne.’” Lieutenant J. Hampden Chamberlayne was the aid to Walker.

This is the only account I’ve found describing how and by what road the Confederates artillery arrived on Prospect Hill.

On my map/LiDAR image I show how each artillery piece possibly approached their firing positions from the road. My display uses a graphic taken from a field artillery manual of the time. Most show a horse team pulling a limber and gun in the lead and followed another horse team pulling a limber and caisson. In a few I placed the gun in its emplacement with the horse teams and limber/caisson stationed behind in doctrinal distances. No one knows for sure how each team came from the road up through the mature trees. Possibly there were fewer access routes than I depict. Captain Poague describes the area along the road as ‘Dead Horse Hill’. Whether or not Walker’s gunners kept the teams doctrinally positioned or not, there were approximately 200 horses associated with Walker’s 14 guns on the hill in the morning. Additionally, those replacement batteries, like Poague’s, were under Union artillery fire later on the day of battle. ‘Dead Horse Hill’ was an apt term resulting from Union artillery barrages.

Walker’s artillery battalion occupied Prospect Hill on 12 December when Jackson’s Corps took over the defense in this sector. Walker’s battalion was assigned to AP Hill’s division, which provided Jackson’s first line of defense. The location for the guns was selected by BG William N. Pendleton, Lee’s Chief of Artillery prior to the arrival of Jackson. Lines of fire were cleared for the guns. A white oak forest shielded Walker’s guns from observation by Union gunners. For more information (click here).

I wish to thank Frank O’Reilly for his interest in my work and our January 2022 initial field trip looking for the road.

My next blog will explore the 15th New York Volunteer Regiment and the U.S. Engineer Battalion bridging operation at Franklin’s Crossing. This will complete my Engineers of the Rappahannock River series.

Sources:

Books:

O’Reilly, Francis Augustin, The Fredericksburg Campaign, Winter War on the Rappahannock, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 2003. P 131-2.

————, The Fredericksburg Campaign, “Stonewall” Jackson at Fredericksburg, The Battle of Prospect Hill, December 13, 1862, Lynchburg, H.E. Howard, 1993. P 30.

Poague, William Thomas, Gunner with Stonewall, Reminiscences of William Thomas Poague, Jackson, Tenn.: McCowat-Mercer Press, Inc, 1957, P 54-58.

Wise, Jennings Cooper, Long Arm of Lee, Volume 1: Bull Run to Fredericksburg, Lincoln, and London, 1991, p. 377-8 and table p. 284-5.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C., 1890-1901. Series 1. Volume 21, Serial No. 31. http://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records.

No. 305. Report of Colonel J. Thompson, Brown, First Virginia Artillery. December 19, 1862. Pp 639-640.

No. 309. Report of Lieut. Col. R.L. Walker, commanding Artillery. December 21, 1862. Pp 649-50.

Board of Artillery Officers, Instruction for Field Artillery, New York, Van Nostrand, 1864, Republished as The 1864 Field Artillery Tactics by Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, 2005. Plate 92, p 374 and plate 61, p 343.

Maps:

USGS Topo Map, Fredericksburg and Vicinity, showing Battlefields, surveyed 1931. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3884f.cw0556000

Aerial Photo:

Google Earth Image 12/31/2007

Image:

LiDAR Fredericksburg Southwest, on file FRSP.

Horse drawn artillery by Edwin Forbes Horse drawn artillery (loc.gov) LC-DIG-ppmsca-20723

Internet:

Lidar Lidar – Wikipedia, and What is Lidar data and where can I download it? | U.S. Geological Survey (usgs.gov)

You must be logged in to post a comment.