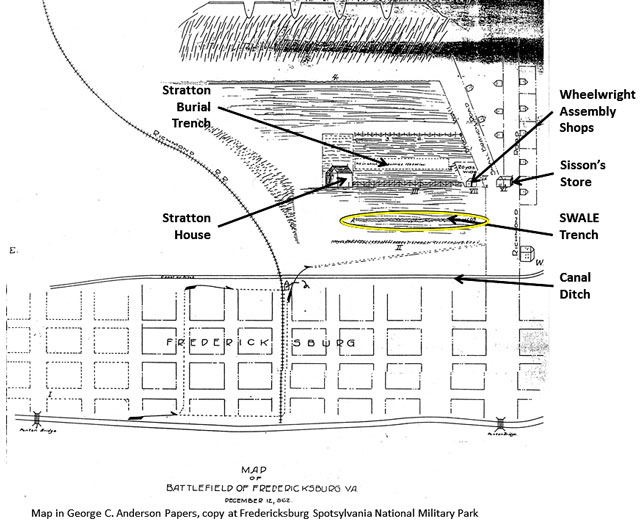

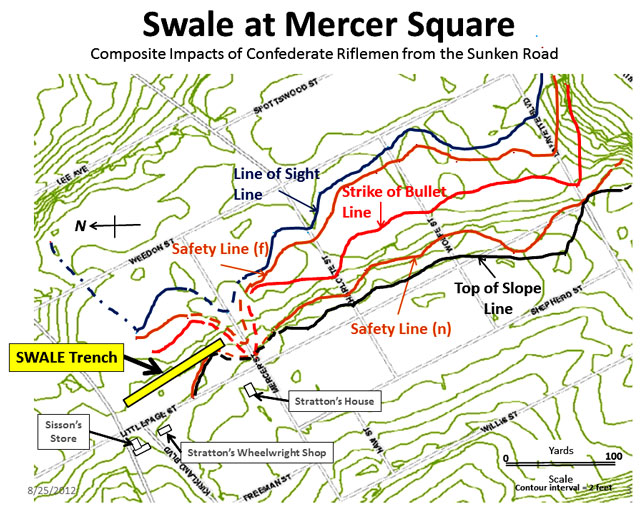

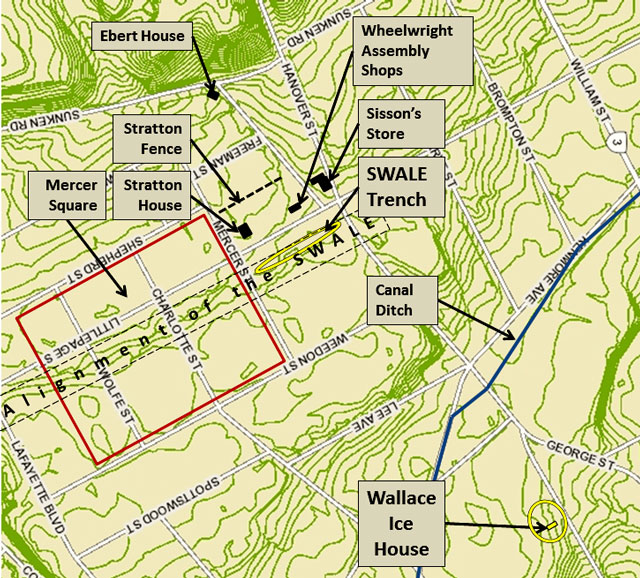

This is the third in a series on the Fredericksburg National Cemetery. I return to the Anderson sketch of the Union burial trenches used in the previous post. These trenches were created to accommodate the large number of Union dead that remained exposed on the open fields in and around Mercer Square following the Battle of Fredericksburg. Now let’s jump to the ‘big’ trench. I call this one the ‘SWALE Trench’. Based upon the work I did finding the Swale in Mercer Square (click here), and reading participant accounts of the battle, I am convinced the location of this trench was along a portion of the Swale from Mercer Street to Hanover Street. The natural swale in this area provided the least protection for Union soldiers that sought shelter there. Further to the south the swale between Mercer Street and Lafayette Boulevard is more pronounced affording more protection.

The George Anderson burial trench map. It provides general information and gives key landmarks; Stratton House, Stratton wheelwright shops, Sisson’s store, and key roads. Richmond Road is now called Hanover Street. The canal ditch stands between the city and the burial area. Marye’s Heights is at the top.

During and following the battle, the Union maintained its units along the swale, preserving their hard fought, or some would say suicidal, gains. On the nights of 13, 14 and 15 December, the Union command rotated units off and onto the line of contact. This line was generally along the swale, as it offered the survivors the best chance of remaining alive during daylight hours. It also provided the Union with an advance departure point in case they wished to renew the conflict. On the first night, the soldiers, individually and collectively, improved their positions by digging in with bayonets and canteen cups. On the second night some units brought out a few shovels which greatly aided this effort.

“…. The rebels were busily at work throwing up additional rifle-pits; and we, finding that the 51st Pennsylvania [Volunteer Infantry Regiment] would hardly be able to finish the elaborate parapet which they were constructing, so as to give us a second chance at their spades, before daylight, set to work upon a ghastly rampart, made of bodies of the dead, ammunition boxes, and the various debris of the battle-field which we could find in the dark, and dig the earth with bayonets and dippers, to give the outside a solid and respectable appearance. Just before day-light we got a spade from the 51st, which did good service as it was passed rapidly along the companies. It had grown quite light, and we saw the famous, massive stone wall under Marye’s Hill, a hundred yards in our front, before the left of the 21st [Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment] got a chance at the spade; but as the rebels were still at work upon their rifle-pits, they allowed us to work on till almost broad daylight, when a single shot was fired from their lines, apparently as a signal for us to stop, and we lay down snugly behind our cover and ate our hard-tack in comparative safety. Our little parapet, although it did not average more than fifteen inches in height, and was very thin in spots, served to conceal us if we lay flat enough, and turned out to be a fair protection against musketry…” Walcott, p 247-8.

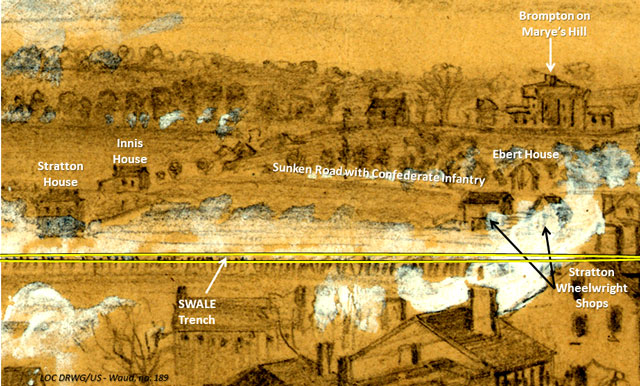

Alfred Waud sketched the Battle of Fredericksburg from atop St. Georges church tower. This is a small portion of that drawing. The location of the future SWALE trench is highlighted in yellow along the line of Union troops firing at the Confederates. The Union troops are aligned along the Swale between Hanover Street to the right and Mercer Street to the left.

“ … The slaughter upon our right [of Ferrero’s Brigade] – where the troops are said to have been more exposed and to have approached nearer the enemy – was greater…The men threw up a little parapet of earth and rubbish, particularly on the left of the [35th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry] Regiment which was more exposed, which did good service as shelter from sharpshooters when daylight came again.” Thirty-Fifth Massachusetts Regiment, p 91-2.

The Union troops withdrew under cover of darkness and rain the night of 15 December. When the Confederates awoke on the morning of the 16th, they discovered the Union army had withdrawn across the river. This type of withdrawal is one of the most difficult for units in contact to successfully accomplish. While the Union army may have been defeated, they were still an army in being.

Confederate artillery gunner John Walters, a member of the Norfolk Blues Light Artillery, participated in the Battle of Fredericksburg. His unit was positioned on an extension of Marye’s Heights north of William Street (Plank Road) on what is now the University of Mary Washington. His diary captured the scene of devastation he found in the city and on the open plain around Mercer Square.

“December 16, 1862. Contrary to all expectations… about eleven o’clock am we learned that the enemy had evacuated the city, … Wishing see in what condition they had left the city, in company with some of our boys, … I found the city a wretched sight, three or four squares burned to the ground, churches and dwellings riddled by shot and shell and many of the latter entirely demolished, while the streets were full of destroyed furniture, books, papers, and dead horses. While in many gardens, lanes and house porches were lying dead soldiers in every conceivable shape and position, some recently dead, while many, possibly those slain the first day of the fight, were far gone towards decomposition, the whole presenting an appearance such as I never care to see again…. After looking around for some time I went to the field from which the troops charged our batteries, and here the sight was horrible. ‘Tis true the wounded had been removed and were not there to fill the air with those ‘oft written about shrieks and groans, but six or seven hundred lay strewn around, from whom our men were busily engaged in removing the clothing and other articles of value. I did a little in that line myself and got an excellent knapsack (empty), a haversack, a canteen, and four one pound bars of yellow soap…”

“December 17, 1862. The enemy was busy all day in removing, and sent over a flag of truce to bury their dead…“ Walters, p 49-50.

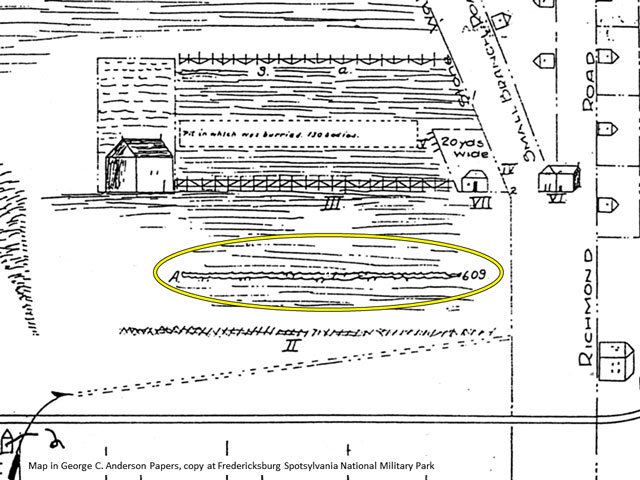

Detail of the George Anderson map. The SWALE trench circled in yellow contained 609 bodies. It was located between Hanover Street on the right and Mercer Street on the left. 100 yards long by two yards wide accommodated three layers of bodies laid out side by side.

The Union sent over a burial detail on December 17th. This detail included 50 men from both the Second and Ninth corps. It returned with 200 men, twice the size on the 18th, having left at least 400 unburied following the first day’s effort. Colonel John Brooke commanded the Union burial detail. He lists 918 slain and buried. This includes 130 in the ‘Stratton’ trench, 609 in the ‘Swale’ trench, as well as five officers’ bodies taken back across the river. This total leaves 174 buried but unaccounted for in his report. This last group were buried in location(s) other than those covered by the Anderson map. Looking at the breadth of the fighting below Marye’s Heights, the front line would have stretched over 1,100 yards from the unfinished railroad at the southern end to the Hurkamp tannery on William Street at the northern end. Given the state of decomposition four to five days after the battle, the task of collecting bodies and parts of bodies, troops, if not closely supervised, would have been very tempted to make use of convenient locations to dispose of the bodies. Some bodies were also unfortunately overlooked.

This January 2012 photo shows the alley looking west between Hanover St. on the right and Mercer St. on the left. In the background is Littlepage St which at the time of the battle was called Fair St. Note the slight rise in terrain as the alley nears the street. I marked the approximate area of the SWALE trench in yellow.

We have this short account from the 35th Massachusetts; “On the 17th of December the regiment joined the brigade… Captain Lathrop was sent, under a flag of truce, in command of a detail of fifty men of the brigade (ten from the Thirty-Fifth) to assist in burying the dead upon the battle-field of Fredericksburg. The detail was allowed to approach the stone wall as near as there were any bodies found lying. They buried one hundred and eight men that afternoon, nearly all of them stark naked, their clothing having been stripped off by the enemy…“ Thirty-Fifth Regiment. p 93.

“…The dead were all buried in the trenches that had been thrown up during the fighting.” Sauers, p 102. The Swale Trench was approximately 100 yards long, two yards wide and sufficiently deep to accommodate bodies laid three deep, with dirt thrown between and on top. Some observers noted that following the winter rains, some bodies were exposed to the ravages of feral dogs. Unfortunately, none of the burial trenches or locations were marked, which added to the confusion when it came to post-war reburial in the National Cemetery.

This photo is taken from Littlepage St looking east. The approximate location of the SWALE trench is marked in yellow. Modern development altered the terrain along the swale to accommodate houses and the streets.

Benjamin Borton, a former member of the 24th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry Regiment, published his experiences in 1903. He traveled in the South on several occasions following the civil war. He interviewed former Confederate soldiers during his visits, including some of these in his book. On one of these trips, Borton revisited Fredericksburg. He hiked to Falmouth to see his old winter campground and then on to the other side of the river, venturing as far as the National Cemetery and the Sunken Road. Borton quotes former Confederate, Captain C.H. Andrews of the 3rd Georgia Volunteer Infantry Regiment, who related a trip to the Mercer Square killing field in January 1863, a month after the battle; “… A short distance nearer the city [from the Sunken Road], and where the open field made a sudden dip or step, was a line of earth-works, thrown up hastily as a protection against the bullets of the Confederates, and in this earth-work defense …dead horses were placed, and with them had been laid the bodies of dead Federals, for here and there the legs of horses and arms and legs of soldiers thrust out, and over all loose dirt was piled, intended to cover and bury them. It shocked us greatly – the inhumanity to brave, dead and now helpless comrades.” Borton continued his account by Captain Andrews “… We examined the framed house – Stephens – and noted that at a little distance from the wall towards town, were several small framed houses had been enclosures as if for gardens. That near those houses and nearer the city had been a well, from which the curbing had been removed, and the well was filled with federal soldiers, tumbled helter-skelter, arms and legs protruding in every directions.” Borton, p 232.

Topo map of the Swale in Mercer Square created in 2012 to show the limits of protection of the swale during the battle. I added the location of the SWALE trench. My mapping cuts off on the left side due to the unclear nature of protection in that area. Union troops would have had to dig in to add protection in this location.

One of the additional burial locations was an ice house located on Hanover Street. It was used as a convenient mass burial site on the city side of the canal ditch where a number of Union casualties from Confederate artillery had occurred. Another Confederate, Major W. Roy Mason, was quoted; “…The day after the battle, Sunday, I witnessed with pain the burial of thousands of Federal dead that had fallen at Fredericksburg. The night before, the thermometer must have fallen to zero, and the bodies had frozen to the ground. The ground was frozen nearly a foot deep and it was necessary to use pick-axes. Trenches were dug on the battlefield, and the dead collected and laid in a line for burial. It was a sad sight to see those brave soldiers thrown into the trenches, without even a blanket or a word of prayer, and the heavy clods thrown upon them; but the most sickening sight of all was when they threw the dead – some four or five hundred in number – into Wallace’s empty ice house, where they were found, a hecatomb of skeletons, after the war.” (Emphasis added) History of the 127th, p 134.

Wallace Ice House. This structure was located on the lower slope of a large house and property called Federal Hill. The ice house was dug into the hillside to insulate the ice. It had a simple peaked roof for sun protection. The left front supports of the roof were damaged by Confederate artillery fire during the battle in this 1864 photo. You can see Hanover and George Streets out which Union troops moved from the city behind you towards Marye’s Heights in the background. I also marked the approximate location of the SWALE trench.

Heros von Borcke who was General JEB Stewart’s chief of staff provided the following observation; “…I was painfully shocked at the inevitably rough manner in which the Yankee soldiers treated the dead bodies of their comrades. Not far from Marye’s Heights existed a hole of considerable dimensions, which had once been an ice-house; and in order to spare time and labour, this had been selected by the Federal officers to serve as a large common grave, not less than 800 of their men being buried in it. The bodies of these poor fellows, stripped nearly naked, were gathered in huge mounds around the pit, and tumbled neck and heels into it; the dull “thud” of corpse falling on corpse coming up from the depths of the hole until the solid mass of human flesh reached near the surface, when a covering of logs, chalk, and mud closed the mouth of this vast and awful tomb. Heros von Borcke, p 148-9.

Topo map showing the location of the SWALE trench and Wallace’s ice house. A number of Union casualties occurred while troops were held up attempting to cross what remained of the Hanover bridge or waiting their turn to cross.

I suspect that Union dead who lay at the extremities of the battlefield were also buried separately. Given the size of the task, Union soldiers previously incorporated into the defensive works, likely remained untouched.

The killing ground in and around Mercer Square. The SWALE trench was located in the most exposed section of the swale. Union troops deepened the swale in this location to increase the amount of protection that it provided. The Wallace ice house became an ad hoc burial pit for casualties in its vicinity.

Immediately after the Civil War, the author John Trowbridge toured the South, to include a tour of Fredericksburg with a local guide. He provided the following scene of locals replanting in Mercer Square in 1865; “He invited me to go through the cornfield and see where the dead were buried. Near the middle of the piece a strip some fifteen yards long and four wide was left uncultivated. ‘There are a thousand of your men buried in this hole; that’s the reason we didn’t plant here.’ Some distance below the cornfield there was the cellar of an ice-house, in which five hundred Union soldiers were buried. And yet these were but a portion of the slain; all the surrounding fields were scared with graves.” Trowbridge, p 112.

The number of bodies actually recovered from the ice house was lower than the rumored/reported number. Some say as low as fifty to one hundred. Records are unclear and the contractor handling the job was fired for questionable practices. Records show just thirty-nine bodies were removed.

In this and the previous post I covered Union burial activities that resulted from the Battle of Fredericksburg. In my next post I will look at the creation of the National Cemetery. I will also summarize the burial efforts, and for quite a number, non-burial of Union soldiers, many of whom simply lay where they fell, in the subsequent battles of Chancellorsville, Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House.

Sources:

Books:

Borton, Benjamin, On the Parallels or Chapters on Inner History, A Story of the Rappahannock, Woodstown, NJ: Monitor Register Print, 1903, p 232. https://archive.org/details/onparallelsorcha00bort

Committee of the Regimental Association, History of the Thirty-Fifth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, 1862-1865, Boston: Mills, Knight, 1884. p. 92-3.

Harrison, N., Fredericksburg Civil War Sites, Volume 2, Lynchburg: E. Howard, p. 172.

NA, History of the 127th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, Lebanon, PA: Press of Report publishing Co. 1902, p 134.

O’Brian, Kevin E. Editor, My Life in the Irish Brigade, The Civil War Memoirs of Private William McCarter, 116th Pennsylvania Infantry, Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1996, p 185-6.

O’Reilly, Francis Augustin, The Fredericksburg Campaign, Winter War on the Rappahannock, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003, p. 459.

Pfanz, Donald, Where Valor Proudly Sleeps, A History of the Fredericksburg National Cemetery, 1866-1933, Fredericksburg: unpublished manuscript, FRSP, 2007. p 18-22.

Sauers, Dr Richard A. editor, The Civil War Journal of Colonel William J. Bolton, 51st Pennsylvania, April 20, 1861 – August 2, 1865. Pennsylvania: Combined Publishing, 2000. p 102.

Trowbridge, John Townsend, The South: A Tour of its Battle-fields and its Cities, Hartford CN: L. Stebbins, 1866, p 112. https://books.google.com/books?id=sB4SAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=trowbridge+the+south&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiXnayb1e_SAhVIzIMKHdh2DykQ6AEIGjAA#v=onepage&q=trowbridge%20the%20south&f=false

von Borcke, Heros, Memoirs of the Confederate War for Independence, Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1867, p 144-5, 148-9. .http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0008%3Achapter%3D18

Walcott, Charles F, History of the Twenty-First Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers in the War for the Preservation of the Union 1861-1865, Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1882, p 247-8.

Walters, John, ed Wiley, Kenneth, Norfolk Blues, The civil War Diary of the Norfolk Light Artillery Blues, Shippensburg: Burd Street Press, 1997, p 49-50.

War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C., 1890-1901. Series 1. http://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records

OR XXI, No. 76, Report of Col. John R. Brooke, Fifty-Third Pennsylvania Infantry, p 261-2.

You must be logged in to post a comment.